A new body of work on the wall for Chichester Open Studios this weekend and next. Do tell your friends to drop by.

“The Trees of India” explores some of the relationships (political, religious, ecological, cultural) Indians have with their arboreal flora. Giclee printed limited editions on Hahnemuhle Hemp.

The Trees of India

Trees call to me. I am drawn to their daily stories through their trunks and bark, the angle of a leaf to the sun and wind, leaf bite patterns by marauding insects. I once stood in a plaza in Seville with a poet’s bust, and at each end of the municipal planting were two huge ficus trees planted in pairs well over a century ago. My husband raised an eyebrow and said ‘Listening?’ as he read aloud about the poet from his phone. I couldn’t take my eyes off the years of growth woven into the girth of these huge trees, and felt their living so strongly. It was as if they were pulsing energy at me. I left them reluctantly, dragging back to the poet, but the four sentries stay in my mind still. The planting done with intent, an urban planner distant in time recognising the necessity for urbanites of green and leaf. The juxtaposition of built and growing. The human need for green and living.

In Cal Flyn’s book ‘Islands of Abandonment’ she discusses Ingo Kowarik’s studies of abandoned post-war railway sidings in Germany. He writes a new framework expressing how we might examine and understand the significance of the patterns of re-growth in flora and fauna in these abandoned sites.

The framework notes four types of vegetation. First, remnants of what we might call pristine nature- undisputed sites, ancient woodland, valuable for their diverse and dense structures. Following this are cultural landscapes, where nature has been shaped and sculpted by farmers and foresters. Think of the sheep, grazing the West Sussex Downs. Or the water channels of Jodphur. Thirdly, ornamental planting of trees and plants, urban planning for aesthetic reasons. Our trees standing sentry in Seville, or the planting of the palm trees along Bombay’s green Maidan.

Finally, Kowarik writes of ‘nature of the fourth kind’: the spontaneous ecosystems that have grown up on wasteland, unsupported. The wastelands I’ve seen are not uninhabited but areas of urban decay, ecological rallying as unintended consequences of urban atrophy.

Peepul leaves, synonymous with temples, sacred groves, city trees and any tiny crack in the masonry.

This feral growth often happens in buildings where ownership is contested. In the heartland of Colaba, Bombay, is a section of building with the roots of a Ficus that wrap themselves around the front face of the structure. A fifty year old legal debate has left the building to the ravages of the monsoon and the humidity of the maritime climate, and unchecked, the tree has taken a firm grasp. To the extent that its roots are partially whitewashed as a nod to keeping it managed. The plant is feral and acts as a support system to the insects, mammals and reptiles living in its crevices and on its bark. Not quite abandoned as a site, the building offers refuge for the tree, and allows the tree to find its own way, the roots and building becoming one. Refugia for wildlife, as Flyn writes. Perhaps the human inhabitants of Colaba might think about the ecological virility of this almost-abandoned building. But it’s too risky: the ficus might uncurl an air root too ambitious, and the thoroughly modern, functional building next door will have to bat off its arboreal advances.

Further north from Colaba a tenement building sprouts another Ficus, its roots finding tenacious hold in the crumbling masonry of the fourth floor. Sharing its position with satellite dishes and illegal verandas, the tree is a subset of Ingo Kowarik’s fourth kind, a feral plant, definitely unsupported but living on a site not yet abandoned. The tenement is fiercely lived in, an urban shout, despite the monsoon’s best attempts to encourage black mould and the city’s pollution a second skin thick on the building. I’m left wondering if the occupants of the building might quite like their airborn tree, so high off the ground, surviving in the traffic vapour trails, an ecological third finger up to the establishment. In solidarity with the apartment dwellers surviving the everyday.

The specificity of the maiden. A broad reach of colonial grass (British grass species do not thrive in India but the homesick Brits loved their lawns) where afternoon cricket could be played, and the heat of the day diminished by the long line of coconut palm trees and its margin. Trees planted for inhabitants to enjoy. (The line of change hard written into the DNA of the architecture. Bombay-Gothic on one shore. Thirty years of structural engineering and backfilling the shoreline, to create the new coast of Art-Deco Bombay). The tropical trees perhaps reminding the city’s inhabitants that they were definitely in India, despite the architectural echoes of Whitehall. Although frankly, with the humidity and the heat and every crack in a wall or the pavement filled with constant growth and green living plant life, there would be little need for reminders.

Bombay still explodes with trees at every turn, although hugely at risk from infrastructural and urban development.

Flyn writes briefly of ‘the ghost of herbivory past’. I like this as an idea. Browsing animals leave ecological traces that reach forward in time, where soil is manure enriched, and there the browsers leave, the uneaten plants come to dominate. ‘A legacy of what comes before. It is a form, they say, of ecological memory’. In the early days of Mumbai’s history, the mangroves and the shoreline trees would have been species typical of those found on the Indian Ocean.

The palms along the Maiden rustling in the breeze are an ecological legacy of Mumbai’s maritime position and history. The British were dependent on maritime trading routes out of India, in the days of the Honourable Company, and Bombay was a big port. These palms, neatly planted and controlled in a green space central to Bombay’s identity, might remind us what came first. Might this be read as another green third finger up to the colonialists, who planted a species for shade and the sound of the breeze in the fronds, and instead grew living reminders of pre-colonial India. It’s an intellectual stretch of an argument, I know, let down by not knowing who planted the palm trees and when. But it is a possibility.

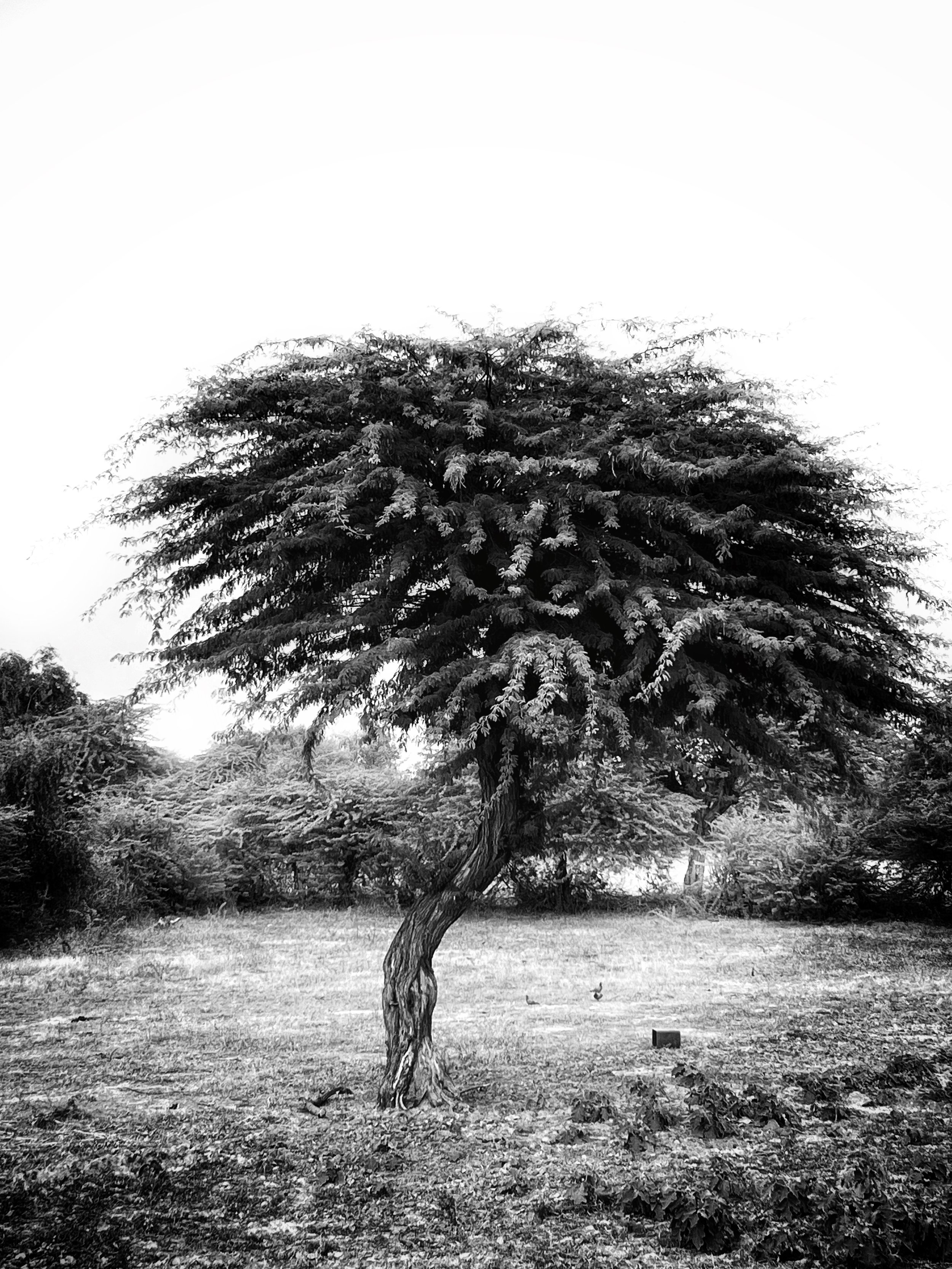

Moving westward to Gujurat and Kutch, the bent trunk tree I photographed here was a species I did not recognise. I was told it was a tree of Spanish origin, the seed thrown from the cargo doors of aeroplanes under Rajiv Gandhi’s re-forestation project of Gujurat. (I have yet to find details of this programme and research continues). These, then, are trees as political statements, supporting farmers needs for more forestry in habitat-depleted regions, encouraging the agricultural vote. We doubled back so I could photograph it, it’s odd bent trunk and bushy head standing out like a sore thumb. An ecological memorial to a political act.

In South India, the tree species changes. The Nilgiri Hills are a protected biosphere region I know well, and walking trails through Thekaddy I have seen fantastical trees trunks that curve to the sky, and drowned trees in the Periyar Reservoir testament to water management in the 1930s. The tea estates of the Nilgiris offer extraordinary vistas, and some of my favourite images are of the tea bushes like terrestrial coral formations, punctuated by tall Silver Oaks. This is very much a cultural landscape, the planting of tall Silver Oaks to stabilise soil and give shade to the intensively farmed tea bushes below.

Northwest to Rajasthan, in Jodphur, the Maharani (or queen) historically took responsibility for water management. No doubt another political move to encourage the dominated population to love their rulers, (and their queen) the water tanks and lakes are nonetheless testament to the public works she carried out. One of these is a rain gorge, the Hathi Nahar or elephant walk. A water catchment channel chiselled out in the 1500s where two types of rock strata existed. When the rains fell, water was channeled down the gorge into a rainwater lake designed to manage flow to hydrate the Brahmins of Jodphur through the dryer periods. Out of the monsoon one can now walk its high-walled path, lined with local species of acacia and other desert plants. The trees follow the gorge, and looking up one can see their branches high against the sky. This walk is a recent development, a desert biome walking trail that leads and educates people through its paths. India’s recent explosion in middle class tourism has pushed out new ways of being a tourist, with nature more celebrated. Native species are signboarded as drought resistant and therefore special. Ecological sensitivity comes with economic growth. The tourist gaze is shifting.

Forever and always, the role of the tree in the subcontinent as a transmitter of prayers and offerings stands strong. Every village has its temple, and at every temple stands a peepul tree, often festooned with red or orange fabric or tied with sacred thread. All blessed by the priest, purchased from the religious bits vendors lined along the road close by. Prayers are offered, cotton or chiffon is tied to the tree, which both takes the blessing and carries the prayer to the god(s). The tree is as significant as the religious finery it wears. I love these holy trees and have to stop to photograph them. Around the lake at Pushkar the trees have incense lit twice a day at their roots, a smoky prayer sent heavenward, both a thanks to the tree and a useful daily godward invocation.

Under the shade of India’s holy trees, villagers gossip, chai made and sold.

Holy trees are rarely cut, and some temple trees can be two or three centuries old. Trees that clean the air, are refugia for insects and reptiles stranded in urban environments, have vermilion blessings from their community of temple goers. These trees, holy by geographic proximity, are both protectors and protected.

The huge peepul trees in Colaba offer shade and protection. The trunk gives the barber somewhere to hang his mirror, or locals rest beneath their shade, phone calls carried out. These trees are more than just urban landscape design. They remind the Bombayites of their village roots, connecting people to nature, allowing cultural behaviour to shift from village to city with familiar landmarks. All over India I have seen walls built with tree branches given space to go through rather than cut. I’ve seen trees garlanded for festivals, threaded for luck, lit joss sticks stuck into the root trunks of the aerial ficus. I’ve walked in sacred groves and city parks from North to South, sat in the shade of village banyans.

This is a land that loves her trees.

This is also a land of new development, metro line building, housing construction. Old street trees are at risk right across Mumbai, and have been cut down in their thousands. Pockets of resistance have limited voice against the municipal authorities and wealthy developers. This is not the space for this discussion, but it needs the oxygen of publicity.