My apologies to John Keay. I first read his book in the early nineties, and have read it a good few times since. I have been thinking and reading about trade routes through the Himalayas and the role ponies played in trade, and I’ve been lucky enough to spot another moment where my interests collide. The production of pashmina shawls is supported by wool from goats in the mountains. When I’ve been reading about products “…such as wool” from the mountains was traded up and down on the backs of hardy ponies from the Spiti Valley, some of this was wool for pashminas. I can’t believe I haven’t twigged before. I thought it was any old wool. Or must have missed the connecting moment. An intersection of my interests where men and mountains meet.

The tour in November 2023 is a textiles trip, taking a good, long look at the artisan production of hand-crafted textiles in Gujurat, specifically around the textile hotspot of Bhuj. I’ve been leaning into reading and learning about how people make use of the resources around them in Bhuj, how environment influences colour and design, and how people have traded resources to create the textile they needed.

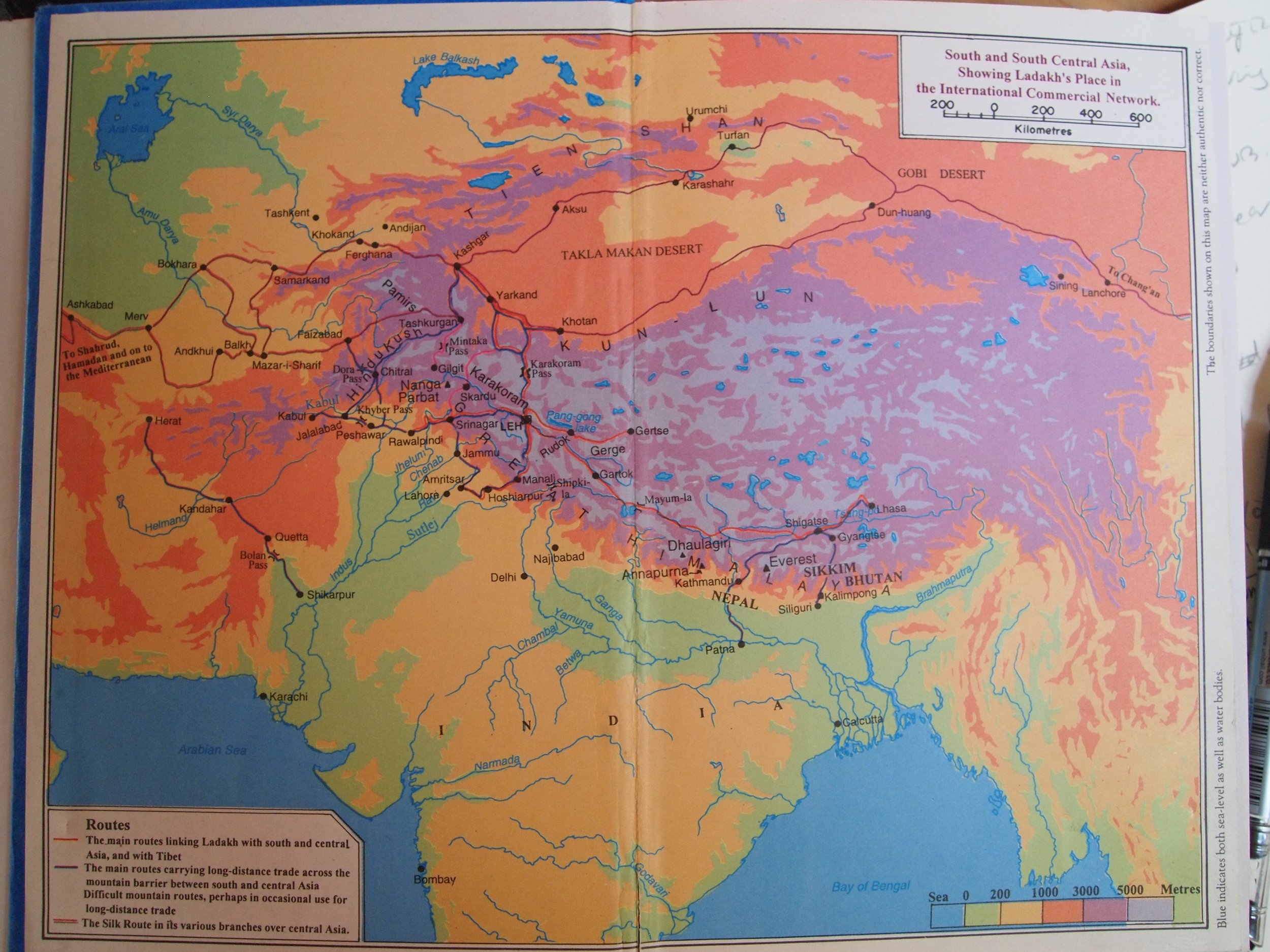

Which reminds me of a trip I took ten years ago to Ladakh, exploring the roles of little local Zhanskari ponies of the Himalaya in trading and trading routes. The porosity of the mountains that seem an impermeable barrier to those not living there. I skittled the kids along with me, and we went all the way out of Leh to meet the Changpa nomads herding goats on the Changpang Plateau, up at a breathtaking, heart stopping 4500 metres.

Before we go any further, I have to admit to a passion for handmade shawls that is wholly self serving.

I love the feel of hand woven, the irregularity in the perfection of hand made. I have traditional Himachal deep brown herringbone weave shawls with red geometric stripes in the weft at each end, bought over the years from my educator and friend in many things woven, Sita Ram in Manali. When Jack was born he sent me an exquisite cream baby shawl in a wool/angora mix, the product of German missionaries in the 19th century in Kullu. I have Sita Ram to thank for explaining, patiently, how the domestic looms in the villages scattered around Manali worked, and (over excellent ginger tea), met the many ladies that spin and knit for him.

I have a deep chocolate cashmere shawl, a sample from the heady days of the Negi-Warner Shawl Emporium that never quite happened for various reasons. A trip through Himachal Pradesh 12 years ago designing big shawls and working on colours was brilliantly educational. Amit Negi and his wife Jane-Anne and I had three children in tow as we felt fabrics and applied watercolour paint to design boards. I had the idea to add an ID mark to each of our shawls, allowing the wearer to go online and meet the weaver, and engage with the slow process of hand weaving. (Oddly a range of strikingly similar designs to ours appeared in the UK a year later which we never got to the bottom of. Shawl design industrial espionage).

The Itch, bought from the Pushkar camel mela, is a hand woven brown number from the spare fur of teenage camels, in a rich burnt caramel, and I have Akrajh, Banjari, hand blocked and tie-dyed, in cotton to silk, from Gujurat, Rajasthan, Calcutta. All hand woven, hand dyed, hand processed. All are precious.

I own Fab India wool shawls with Kullu designs, simple grey and black shawls bought from my textile guy in Jaipur, and the first shawl I bought in my early twenties in Bombay. Mis-sold as cashmere to my young uneducated eye, it is a simple duck egg blue with exquisite cream embroidery from Jammu and Kashmir. I can safely say it triggered the collection. I imported Himachali wool shawls embroidered in crewel, selling textiles with Trunk Sales from my farmhouse, and I’ve been in love with India’s shawls from the moment I landed in Bombay. Following the route of the pashmina shawl back to its raw material makes total sense to the geographer in me.

The mountains are the Zhanskari Range, a flight up from Delhi where the runway suddenly appears in a valley walled by massive mountains. A road trip 80km out of Leh to the east, overnight in a truck stop with beery truckers and a huge army officer worrying about our safety. The road pretty rough and in constant state of mend with JCB machinery, kept operational for the many military trucks winding their way to listening points on the high Indo-Chinese borders. And incredible views of unimagined landscape, punctuated by massive Buddhist monasteries. Oasis of wealth and patronage, religion, culture and art. From a Western perspective these huge monasteries feel they’re in the middle of nowhere. To Buddhists from the region, these monasteries are close to Buddha’s roots.

The other inhabitants of the dry desert in this part of Ladakh are the pastoral nomads. This term has a depth of academic research behind it examining settlement and ways society has evolved, delicious ways to spend time for a geographer. If agriculturalists live from domesticated plants, the pastoralist lives from domesticated animals. Smaller populations can be supported on animals than agriculture (the food chain/energy principle) so populations are thinner, often existing where there is low rainfall, poor soil and farming difficult. Where the grass is poor, grazing is also limited, requiring the movement of herds. In turn, this leads to nomadism. The Changpa nomads are not fully nomadic, as they live in sheltered winter camps and walk their herds into the high pastures of the Zhanskar range in the Himalayas. Uphill in the summer and downhill in the winter, they practice a form of transhumance. The goats are one of three species found in Ladakh, Tibet and Nepal, and in Ladakh are called Changthani. Gorgeous creatures with coats that range from deep chocolate to cream, the goats are the backbone of family income.

The Changpa gentleman I met talked to me about moving his goats in a circular route, leaving on auspicious days as advised by the Buddhist Langna Rinpoche at the monastery in Korzok, elders, and the shifting of the seasons. (Fully nomadic people do not follow specific circular routes). He talked about how wool prices fluctuate, and as he skilfully removed wool from a pelt, whether his children would stay with tradition. While we were there a young mother of the village group came over to ask him some questions, her small girl gazing over the huge open landscape, silver baubles on her pink hat sparkling in the July sunshine.

His wife made us yak butter tea in the tent, a semi-permanent hole with some stones in the walls and a yak-woven fabric for the roof. One of his daughters was the same age as mine, and spoke English from winter school in Leh. We chatted about homework. They bonded.

The family were wearing homemade wooly hats, and along the road at various tea shacks were hand knitted socks and hats for sale as income income supplements. In my research I’ve picked up a creator story about why the shawl industry started in J&K. A 15th century Sufi saint came from Persia to Kashmir, and on a 1400s road trip to Ladakh (the mind boggles) noticed that the mountain people had the raw materials for a weaving industry to jump-start economically poor Kashmir. He ordered up a pair of socks which he gifted to the king. The king, Zain ul Abideen, loved the socks so much he set up weavers to be trained by the Saint’s guys from Persia. The sock story demands more attention I feel. But it does point to old trading routes and the supply in trade between pastoralists and agrarians.

The interdependency between nomads and goats is based on climate. The goats put on fur for the cold winter and moult it in the warmer spring, given a judicious hand by the Changpa who comb the goats in spring to encourage the fur removal. The goats are unharmed by the process as it is their seasonal moulting period, and I can attest to having seen some awfully scraggy coats of moulting goats, so the combing of these beasts at the moment when they need it seems sensible for both goats and nomads. I wonder if the coat scraggle is now dependent on a good comb, as these two mammals have been interdependent for a very long time.

The winter-underduvet of the Himalayan Changthani goat local to Ladakh has the finest, warmest hair at between 10-15 microns, and is considered the finest raw pashmina source on the planet. India contributes about 1% to global production of cashmere wool and the best comes from these fiercely difficult mountain environments. This tiny fibre is counted in 50-100 milligrams per goat per moult. It is clear the production of pashm fibre is a hard-won living. Once spun and then woven it becomes pashmina.

I didn’t know then that the nomad’s existence was so threatened.

The gentleman I met expressed fear that his children would not want to continue the harsh experience of one of the coldest winters on earth at -40 degrees. The colder the winter, the more the goat under-duvet. The colder the winter, the warmer the possibilities of a built house in Leh. We all live in a modern world. We talked of homework and we talked of Leh in the winter. Bertie’s new friend said she preferred the winters in town.

From the research I’ve done recently, it seems that over the ten years the number of nomad families still running goats has dropped to sixteen. This seems to me to be an unsustainable amount of pashm fibre for the needs of shawl sellers in Jammu and Kashmir, and beyond. This could be an artisinal industry on the verge of collapse.

The attacks are multiple. Warmer winters are leading to increased rainfall and less snow. In turn, goats put on less winter fur, and it’s less fine. More rain is messing with vegetation patterns, and winter feed is being trucked in as government subsidies to prevent goat starvation.

The Tso-Moriri Lake area bristles with antennas and checkpoints. Military sensitive since China expanded its borders in 1957, this region is awash with army and borders are secure. The transient, traditional ways of the tribal families are no longer supported by porous border access. Pastures once reached as part of the pastural migration are not necessarily legally accessed. The wider trading into Tibet for pashm was cut off at its knees when border security tightened, the knock on impact being significant rises in the value of the goat fibre but also increased pressure to have goats on the same high pastures. This was never a high value, fast output activity. This was a seasonal dance, the nomads dependent on their animals, in turn dependent on them.

Other causes of concern to the wider industry are the ladies who spin. Many of the traders coming into the region sell the wool in Jammu and Kashmir. This fellow in a very covetable hat and highly necessary shades was walking to Leh, perhaps three days out by foot. The ponies trundled on without him, and he had to cut our questions short as they disappeared into the big blue vista. His wool will be traded into the network of buyers that sell on to the weavers and shawl houses of Kashmere.

The wool predominantly finds its way to Jammu and Kashmere, with Srinagar a centre of weaving and then embroidery. Once the raw wool finds its way into the system, it is then spun into thread, and this is then woven on hand looms. Traditionally a domestic, piece-work industry, done by women at home, the appallingly low rate of pay for spinning have made it an uneconomic choice. At 1 rupee per thread, women were leaving their generational practice and looking for work elsewhere. Spinning is traditionally a slow, drawn out affair, with the 250-500 milligrammes needed to make enough wool for one shawl taking two months to spin. Critically the staple length is around 1.75-2 inches long, and hand spinning creates a longer staple that is fragile but less breakable than shorter machine-spun pashmina. The shawl itself, a gossamer light creation made from some of the finest handmade natural fibre humans can make, takes a month to weave by hand.

Let us focus on the numbers. The data available on wool production varies but in essence each goat produces low amounts of usable wool from the moult, after being washed and sorted, or carded. Here are the numbers again: approximately 100 milligrams of wool per goat, 250-500 milligrams per shawl, two months to spin the yarn and one month to weave it into a shawl on a hand loom, the fibres too sensitive to withstand the vibration of a power loom, the hard whack of a wooden shuttle against a yarn 12-15 microns thick. India produces 40-50 tonnes annually. These shawls are hard won.

This question of time has led to a number of interesting developments. Somewhat unscrupulous weavers have chemically added plastic to the natural fibre to give it resistance to the power loom. This is then removed, once woven, by a mild acid bath. The fibre shrinks, and pills, and does no favours to the quality of the brand or trust in what is a pashmina. A power loom from Amritsar takes 15 minutes to make a shawl from a range of non-pashm fibres. The value of a pashmina shawl is much higher than a wooden or synthetic shawl, so the appeal to cut corners is strong.

Point of sale is another matter. This incredible yarn deserves to be woven into interesting, modern designs as well as traditional weaving patterns. As Judy Frater says, let the artisans have agency in their designs. Find ways to experience teaching centres like Somaiya Kala-Vidaya in Bhuj. Encourage national and international residencies and collaborations.

Other developments include international sellers of pashmina (or cashmere) shawls looking for ways to up production. The yinder is a traditional bit of kit that winds the spun fibre, to which the enterprising Me and K luxury brand has added a pedal and a dedicated work space. Spinning times are on the up, and same amount of wool needed for a shawl takes 40 days, not two months. The women sit more comfortably, and the Government of Kashmiri has upped the minimum spin wage to 2.5 rupees per thread. Let’s hope the supply of Ladakhi wool is able to keep up.

The Government of Kashmir is slowly realising that it needs to protect this amazing resource (it has been busy with other matters, to be fair) and is doing work using AI technology to geo-identify each pashmina product. As cheddar cheese is to Somerset, champagne is to France, pashmina is to Jammu and Kashmir. There are plans afoot to control pricing and give the pashmina shawl a $160 starting price point, although whether any of this will reach the goats is another matter. There are plans to involve J and K in craft and artisan safaris as their artisan cottage industries are in tatters, post political troubles and post pandemic. It is worth noting that pashmina wool also comes from the high altitude areas of Kinnar, Lehaul, and the Spiti Valley.

The families that endure freezing winters and a traditionally hard way of life are recompensed by the goat fibre having a higher value than before China expanded its borders. But their way of life is definitely under threat. They are a living, breathing pastoral tribal tradition that possibly stretches back to the Harrapan Civilisation 300-400 BCE, Caesar in Rome, Cleopatra in Egypt, the Kushan rulers of Kashmir 1 BCE to 3 AD.

If Kashmir was trading wool on the Silk Route, which academics in the textile world think it was, it seems likely that Pashmina shawls might have been among the first luxury goods traded into the Roman Empire. Marco Polo may have missed this on his travels on the Silk Road but there is strong evidence for the 15th century having documented pashmina production, which is still a good 700 years or so. Every Indian lady has a shawl of some kind, providing a soft physical and psychological buttress against the world.

These historic links through time and space deserve to be cherished and encouraged. At key points along the high altitude roads are Buddhist shrines, prayers sent skyward to Lord Buddha each time a flag snaps in the chilly wind. Votive offerings are laid. I found a goat horn at one, reminding us of the importance of these animals to the nomads living here. They are going to need these blessings.

I wish I had solutions. The value of the goat fibre might increase so much that the tribal children see value in their traditional lifestyle, bringing education and technology back into the community. Old ways can be improved. Goat kids can be microchipped. Husbandry can be improved. Winter food can continue to be shipped in.

I’m thinking hard about how I can do my bit, and three routes play to my strengths. First, this. Reminding us to buy hand made over any kind of power loom. To buy responsibly. To pay properly. Secondly a photographic series on the subject, an ongoing concept I’m working on, looking for collaborations on the ground. Third, responsible, thoughtful, slow textile tours, on the trail of this historic, mesmerising fabric.

Not many visitors make it this high and this far into the dry deserts of Ladakh.

By supporting local community homestays, working with local not-for-profits that work with the tribespeople, and finding ways to be involved that go directly to the herders of these feisty goats, perhaps we can make a little positive difference. Seed balls will be catapulted. Shawls purchased. Artisans supported.

There will be high altitude walking and workshops. You need to be of average or above fitness and generally healthy to participate.

September is a beautiful time to be in Ladakh…

…and I’m looking at a 14 day tour beginning in Delhi and ending in Leh.

Dates and prices to be confirmed but currently hovering around the second and third weeks of September 2024, at approximately £3690 (tbc).

This is an adventure. Do join me on a a journey into the Western Himalayas following the trail of these beautiful shawls. Places are limited to 8 only.

Pop me an email if you’d like to know more, via the button below.

Come with me and see for yourself.