This is not made clear to me or our little gang of photographers until we are well into the mela at two in the morning. We spot a line of press photographers walking past, and I point out to our guide that we could tag along and no-one might notice for a while. He looks uncomfortable but I mobilise the gang and we set off in pursuit. The barricade is up, with police blocking our way, but we manage to slide on through with persuasion from Vimal, and follow the long lenses. Finally Vimal's nerve gives out and he says we are not going to be able to make it to the water. I look at where we are. It seems, after a bit of asking about, the sadhus will be coming this way.

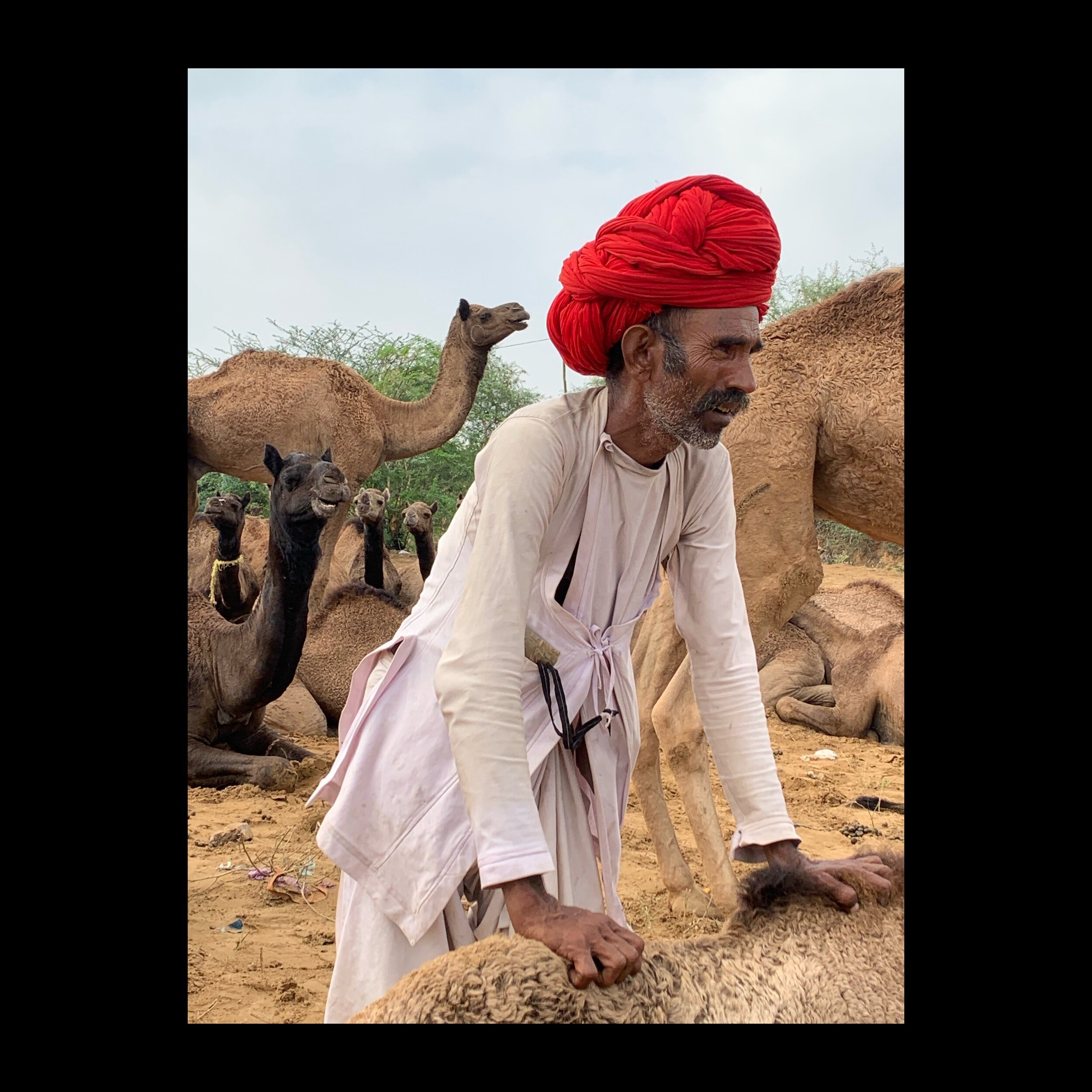

We decide to camp out and relax for a bit. We're on a wide boulevard with huge encampments either side of the road. There are sadhus over fires sitting on the peripheral, and plenty of little groups of pilgrims starting to build. Plenty to photograph, plenty of atmosphere to absorb. We talk about camera settings, make sure everyone is set up and good to go, then take brave little steps across to photograph the sadhus on the other side of the road wth their fire and tridents. Pilgrims want selfies with us. A set of five or six SUV cars bear down on us, off -road and at some speed, dangerously behind the lines of pilgrims. I catch sight of the passengers, and have a weird eye-contact moment with sadhus made-up as ladies but wearing sadhu robes, unusually not crammed with twenty others into their diesel chariots. Vimal confirmed what I thought I had seen, but was unable to explain why they were off-road, why they had come and gone so fast, why they looked like they didn't want to be seen. It was another experience I had to file away for later examination.

We're there for an hour or so until the numbers begin to swell. Little knots of people are coming down the road, all in a hurry, aiming to the water sedge at breakneck speed. Grandma's are being pulled along by hurrying sons, and everyone is in a rush. We're not sure why, but it's something to do with the sadhus coming after them. There are other pilgrims explaining who is coming next, and that the sadhus will be passing this way down this street. By good luck and persistence we are in the right spot.

As the sun starts to come up we are aware there is a large contingent of naked, ash-smeared holy men starting to congregate, all shouting 'Mahadev' and spearing the sky with sticks and swords. There are sadhus allocated to road-clearing duties, and a particularly ornery lady sadhu is keen to keep us all back off the roads edge. Just as keen as the people behind us, pushing forwards. It's a no-win situation, and this proves to be the point a few minutes later. The crowd surges a little and the sadhu lady loses her temper, giving me a tight slap like a cobra unfurling across my jaw. It's so fast and unexpected we all laugh, although I complain loudly at her. The sadhu crowd grows bigger, and the main baba comes into vision. The crowd roars approval, and we are gifted with the sight of the sun coming up and naked Naga babas climbing onto cars, ordering chillums up from the crowd, and waving their sticks at the rising sun, praying and showing off in the same minute. This goes on for about half an hour. And then, with a surge and huge shouts of 'Mahadev', they go past us at a fast trot, heading for their dip in their holy mother Ganga. Towards moksha. Salvation. The road to eternity.

Behind the Naga sadhus come lorries and cars bedecked with gurus and followers, all waiting for the signal, and we circle with our cameras taking pictures of devotees and sadhus on their most holy day of the Kumbh Mela. We have met (other than the lady sadhu/cobra slap) with nothing but interest and kindness. We have made friends with other pilgrims who helped us in the crowd situation, had their picture taken by us, asked for selfies, talked about the mela with us. It has been fascinating.

Then, however, we decide to return back to our camp, and this is where it got really interesting. The volumes of people at the last Mela were estimated to be 65 million over three months. We know the crowd volumes are going to be huge, and so far, the crowd have been big but we've been able to get around. The authorities include local police and the military, all issued with radios, some with firearms. There are wooden slip rails creating one-way funnels, where the direction of people can be reversed or redirected. We walk for a mile or so in the direction of the pontoon 'out' bridge, and find ourselves in a contraflow of slightly wet sadhus who have had their dip, some of them recognisable from the earlier sadhu exodus to the confluence of the Ganga, Yamuna and the mythical Swaraswati. But we are stuck in an elbow of the route, a slip rail blocking our exit.

And behind the slip rail is a crowd like we have never seen, pressing expectantly in our direction, waiting for the barriers to drop and the pilgrims to surge towards moksha. This line of pilgrims have been waiting for the sadhus to have their dips so they can have theirs. We hesitate.

All of us have our cameras out, dangling, backpacks on our shoulders. The word comes that we are to move, swiftly, through a minuscule gap in the slip rail that the soldier is opening for we foreign tourists. The crowd surges a tiny bit, towards the hole. We are expected to go against the flow of this river of humanity, into its eddies and maestroms and slipstreams. I start shoving my long-lensed camera into my bag, helped by the Spanish girls we befriended on the way. In our haste a zip breaks. I stop rushing. I zip what I can closed, reverse my backpack so it's on my front, stick my Nikon D4 in my hand held above my head, clamp the other hand on one of my fellow photographers, and we surge into the crowd. Above us from a watch tower, a soldier is yelling into his radio. "Commander, shut the gate, Now, Now. Now!" I sense his panic. I try not to feel it as pilgrims try to minnow their way through the wee gap and the crowd burst through. The gate holds, and we are in.

I think instead about what an extraordinary thing faith is, rather than what might happen if I fall. Under my feet are bits of clothing dropped, odd flip-flops, shawls, that catch our feet and try to upend us. We can only take baby steps. The crowd is hemming us in, lifting me off my feet, and we keep moving in the direction of the exit pontoon bridge. Somehow we cross the flow of people, thousands deep, and still hanging onto the person in front, we keep going. This river of people has had their dip, and is going the same direction as us now, but our feet barely touch the sacred dust where the three rivers meet. I turn to keep an eye on one of the group, and see she has a small and ancient grandma attached to her arm. Angela is kind and sweet. I am not. I told the grandma sternly to let go of Angela. Angela was fine, although the worry of being responsible for someone else was a not something any of us had anticipated. The crowd moved under its own impetus. I catch sight of the Spanish ladies, one still hanging onto me, and find they have Grandma on their arm now. Why she thought she'd be safer with us than one of her family I have no idea. Did she even know where her family was? Every year many grandmas get 'lost', left behind as the family scarpers off in another direction, away from familial duties.

Our man Vimal, a tall chap on a good day, is out of sight. I can see the inestimable Mr. Pal (sidekick and fixer) armed with our 100 rupee selfie stick, weaving his way off to the side. The Germans (for we have found ourselves an international group) and their amazing guide are still in the pack, and only Vimal is missing. We manage to re-group on the side of the main flow, and start WhatsApping Vimal to try and find him on this extraordinary throng. We try to take stock of this experience, and what it is we have just done. None of us panicked, all of us managed to keep walking and keep calm. We are babbling slightly with the shock of survival. Justifiably we feel like we have had a massive adventure, and as the adrenalin drops, we feel the need to be back in camp.

Vimal appears, stating he is was worried sick about losing us and where had we got to. We laugh good naturedly at him, thanking our stars for Mr. Pal and the German's guide, who was playing with a full pack and kept all of our group safe. Vimal had stood on a car roof in the hope of seeing us, but finally smart phones had done their thing and he had found us. We braved the pontoon bridge back, stopping to take a few images of bathers so we could say we had seen pilgrims bathe at the Kumbh Mela, and we headed for home. On the exit of the bridge we spotted a rowing boat, bravely trying to find its way under the pontoon bridge, a bundle of blankets on the foredeck. It is human-shaped, and we wonder if it was a trampling. Secretly we thank our lucky stars.

It has been an amazing experience. The 2019 Ardh Kumbh Mela.